In the film 8 Mile, a semi-documentary following the struggle of Marshall Mathers, aka, Eminem, there is a recurring scene which plays an important role. The rapper is painstakingly penning the words to what will ultimately become “Lose Yourself”, a few lines of which you’ve read above. Each of these scenes shows Marshall riding one form of rickety public transport or another through downtrodden locales in Detroit. The first time this recurrent clip plays in the film, we see his notebook, pages empty, with only a faint backtrack pulsing through the speakers. He is struggling to find himself, struggling to find the perfect lyrics to lay over the music, and even struggling to keep the pen steady, perhaps a mixture of nerves and the very real physical challenge associated with writing legibly while riding a bus. This is the recap of my ten month bus riding, song writing, soul searching journey in Germany.

Now I have to admit something before diving too deep on this one: The last thing I expected when moving to Germany was my life having any parallels to that of a platinum haired man who shares his name with popular candy treats. That isn’t to say I was aiming low in my expectations for this first work rotation. (So maybe I wasn’t aiming to earn a Grammy or have a date with Britney Spears, but I most certainly intended to do some other cool things during these ten months.) I was prepared for surprises. I was ready to be challenged at work. I was even anxious to be pushed in my personal life. But following in the likeness of a rap superstar just didn’t make it onto my to-do list.

The first time I noticed this peculiar parallel was, you guessed it, on a bus ride. Myself and a former participant of my work rotation program, who is also not from Germany, began discussing the topic of personal identity while returning from Chemiepark Marl. Having only been working in Germany for a month or so at this time, the advice he offered to be open to change was timely. He described how his work rotations in Germany, and his now full-time role in Germany, had really tested his “non-Germanness”. We spoke specifically of watching the people on the bus that day, as it seemed like a very tangible example of what he was saying. “Just watch the people,” he said somewhat withdrawn, “it only takes a few minutes to know that you’re not in Kansas anymore. You just have to want to see it.”

The talk we shared that day was relatively short, but when I stepped off the bus, I suddenly understood something that would stick with me for the rest of my time in Deutschland: I’m Eminem…and this is my recurring film sequence. In the physical sense, I knew that this would only be one of the hundreds of such bus, train and metro rides I would take. But in the more spiritual sense, I think something about that moment, arriving in a town I couldn’t properly pronounce, seeing signs that looked more like word jigsaw puzzles than sentences, watching the subtle ways that Germans are, well, not Americans, I knew a great opportunity had been given to me. The time would affect – not completely change, but perhaps enhance – personality characteristics I’d developed in another world. The question was no longer if the chance to change would present itself, but whether I would be willing to accept it.

Over the course of the following ten months, consisting of one new language, two flats in the Ruhrgebiet, three landlords, four challenging work projects, nine European country visits and a small hard drives worth of photos, the lyrics and rhythm of my song, both on and off the public transit system of Germany, began to take shape. What began as a crass, incomprehensible pelting of shouting tones, a linguistic jumble of exceptions, slowly evolved into a language I not only dealt with, but, by the end of my time, thoroughly enjoyed speaking; what began as trips filled with nerves to the grocery store, bakery or gym, eventually became an opportunity for me to learn a new vocabulary word or make someone laugh (usually when at the meat counter…and almost always at me); and what began as estranged, distant contact with work colleagues and shop patrons, ultimately blossomed into a few lasting friendships.

The talk we shared that day was relatively short, but when I stepped off the bus, I suddenly understood something that would stick with me for the rest of my time in Deutschland: I’m Eminem…and this is my recurring film sequence. In the physical sense, I knew that this would only be one of the hundreds of such bus, train and metro rides I would take. But in the more spiritual sense, I think something about that moment, arriving in a town I couldn’t properly pronounce, seeing signs that looked more like word jigsaw puzzles than sentences, watching the subtle ways that Germans are, well, not Americans, I knew a great opportunity had been given to me. The time would affect – not completely change, but perhaps enhance – personality characteristics I’d developed in another world. The question was no longer if the chance to change would present itself, but whether I would be willing to accept it.

Over the course of the following ten months, consisting of one new language, two flats in the Ruhrgebiet, three landlords, four challenging work projects, nine European country visits and a small hard drives worth of photos, the lyrics and rhythm of my song, both on and off the public transit system of Germany, began to take shape. What began as a crass, incomprehensible pelting of shouting tones, a linguistic jumble of exceptions, slowly evolved into a language I not only dealt with, but, by the end of my time, thoroughly enjoyed speaking; what began as trips filled with nerves to the grocery store, bakery or gym, eventually became an opportunity for me to learn a new vocabulary word or make someone laugh (usually when at the meat counter…and almost always at me); and what began as estranged, distant contact with work colleagues and shop patrons, ultimately blossomed into a few lasting friendships.

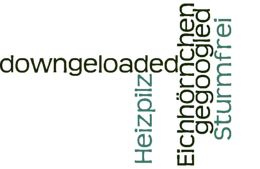

My core was still the same: still Zachary Woods, still from a rural, peach infested town in South Carolina, still a fan of patterned socks, still incessantly goofy, still curious. But when I looked into the internal mirror, the one that reveals much more than if your shirt is stained (it was) or if you’ve gained a few pounds (I had), the person looking back knew something that his former shadow did not – including a newly amassed, clearly important collection of vocabulary words like Eichhörnchen (squirrel), Heizpilz (outdoor standing heater), gegoogled, downgeloaded and my personal favorite, Sturmfrei (when your parents leave for the weekend without you, and the house is free for you to throw a party). And they say the Germans have a tendency to overcomplicate things.

In the process of working, collaborating, eating, laughing and living with the Germans, this reflection had learned about a totally new set of values, about a truly different way of life. I was spending more time enjoying meals, being (slightly) more quite in the work environment, considering to buy full-scale life insurance and listening (a lot) more before speaking. But these were merely the results of a bigger transformation that had taken place: I had developed a willingness to lose myself. Eminem would be so proud.

The Germans, at least for the most part, are not like me. And I, in less ways now as compared to ten months ago, am not like them. Traditionally, this imbalance would have sent me into adaption mode, a condition characterized by adjusting to the surrounding differences just long enough for them to no longer be influential. I am very protective of that core person previously mentioned, and that protectionism has served for quite some time as the proverbial anchor of my personality. This time of sharing with the Germans taught me to see this protectionism in a different light.

I had previously seen this anchor as a way to keep me safe, to keep me being “the person I wanted to be”. This security kept me from deviating too far when a stray wind or strong tide came too close. What I realized was that this anchor had indeed kept me steady, yet it had also kept me from truly embracing the new waters that were just outside the comforts of safe harbor. When a ship sets down anchor, it does indeed protect itself from potentially hazardous weather fluctuations. Yet the other side of that coin is that, by setting the anchor too deep, it also prevents any forward movement. And while there are invariably times it is not only appropriate but wise to set anchor in order to avoid hazardous squalls, with the right amount of guidance and reliance on your sense of internal navigation, there are just as many times when it would be unwise to waste the perfect wind and water conditions that would allow for further personal exploration and advancement.

And now the toughest question of them all: how does one know when to set anchor as opposed to riding the ever-present winds of change? The best thing I can say, using my time in Germany as a guiding reference of course, is to take a cue from the Germans from time to time: listen before speaking, respect their differences of opinion (even if you are totally convinced that they are wrong), eat a pork product that is utterly unrecognizable, etc. Try to understand more about where they’re coming from, why they might have the opinion they do, why they tend to present that opinion in the way they do, and how you, by adjusting yourself – let’s call it “adjusting your sail” for the purpose of continuing the metaphor – might be able to help bridge the gap between these differences. At the end of the day, we are here because of our differences, as well as because of our similarities. Only by sharing your differences with the Germans, and in turn them sharing their differences with you, will there be an overall net gain of intercultural awareness, business effectiveness and personal satisfaction.

The Germans, at least for the most part, are not like me. And I, in less ways now as compared to ten months ago, am not like them. Traditionally, this imbalance would have sent me into adaption mode, a condition characterized by adjusting to the surrounding differences just long enough for them to no longer be influential. I am very protective of that core person previously mentioned, and that protectionism has served for quite some time as the proverbial anchor of my personality. This time of sharing with the Germans taught me to see this protectionism in a different light.

I had previously seen this anchor as a way to keep me safe, to keep me being “the person I wanted to be”. This security kept me from deviating too far when a stray wind or strong tide came too close. What I realized was that this anchor had indeed kept me steady, yet it had also kept me from truly embracing the new waters that were just outside the comforts of safe harbor. When a ship sets down anchor, it does indeed protect itself from potentially hazardous weather fluctuations. Yet the other side of that coin is that, by setting the anchor too deep, it also prevents any forward movement. And while there are invariably times it is not only appropriate but wise to set anchor in order to avoid hazardous squalls, with the right amount of guidance and reliance on your sense of internal navigation, there are just as many times when it would be unwise to waste the perfect wind and water conditions that would allow for further personal exploration and advancement.

And now the toughest question of them all: how does one know when to set anchor as opposed to riding the ever-present winds of change? The best thing I can say, using my time in Germany as a guiding reference of course, is to take a cue from the Germans from time to time: listen before speaking, respect their differences of opinion (even if you are totally convinced that they are wrong), eat a pork product that is utterly unrecognizable, etc. Try to understand more about where they’re coming from, why they might have the opinion they do, why they tend to present that opinion in the way they do, and how you, by adjusting yourself – let’s call it “adjusting your sail” for the purpose of continuing the metaphor – might be able to help bridge the gap between these differences. At the end of the day, we are here because of our differences, as well as because of our similarities. Only by sharing your differences with the Germans, and in turn them sharing their differences with you, will there be an overall net gain of intercultural awareness, business effectiveness and personal satisfaction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed